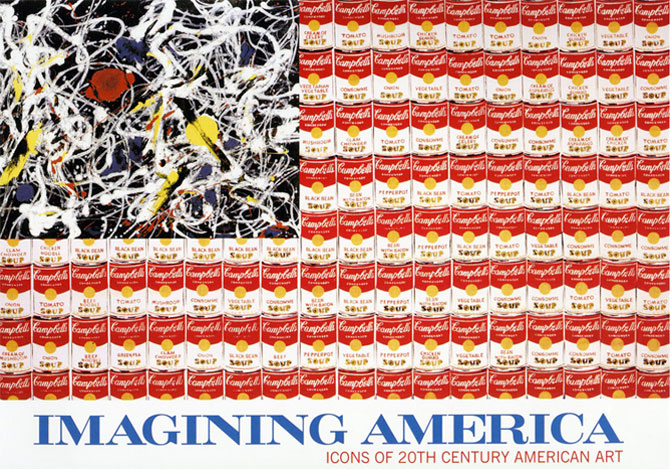

I am an art historian and critic of contemporary art. The particular art theory that has evolved in my writing over a fifty-year career is a social history of art grounded in psychoanalysis and the close reading of objects. This derives from my efforts to understand the dynamics of creativity and how societies use and interact with works of art. This concern drew me early on to the study of child art, where I could see the mechanisms of visual thinking in a simpler form. My forays into computer science and neuroscience have helped me think about the languages of systems and the physiological mechanisms of vision, memory, and cognition that structure what and how we see and think. I have also consistently maintained a personal creative practice, first in sculpture, then in film and writing, and in entrepreneurial creative collaborations such as the two-hour documentary film Imagining America: Icons of 20th Century American Art which I made for PBS television with my friend John Carlin (founder of the Red Hot Organization), and the innovative institutional programs I’ve built at The Phillips Collection in Washington (the Center for the Study of Modern Art) and at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia (the PhD in Creativity, now at Rowan University).

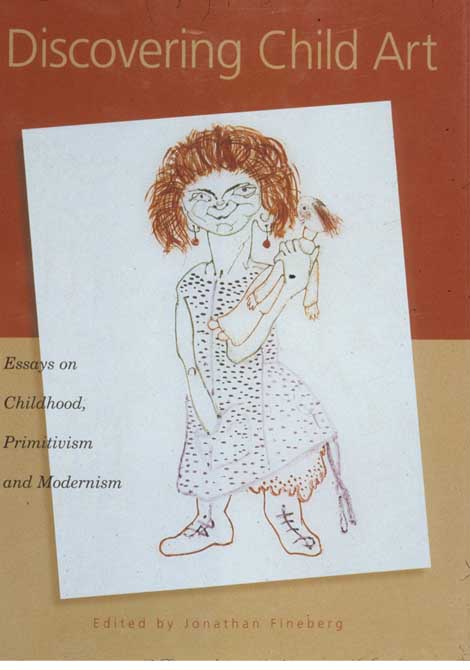

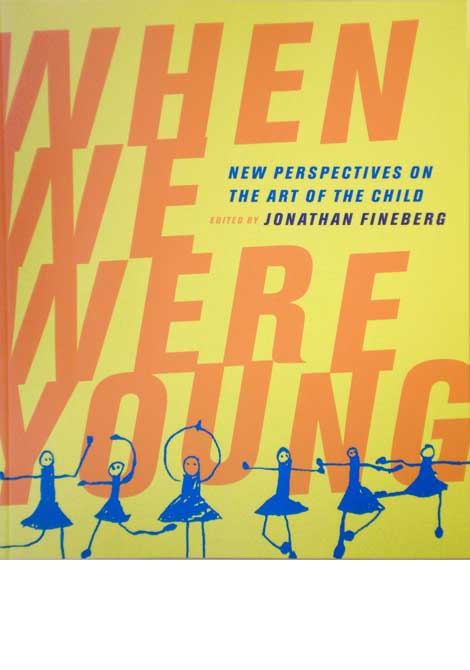

I started thinking about child art and psychoanalysis in my junior year of high school, then abandoned high school after three years to enter Harvard College. There I studied the psychology of visual perception with Rudolf Arnheim, who gave me the tools to make formal arguments on behalf of psychological insights about art. Eventually we became friends and collaborators, as in my edited volumes, Discovering Child Art: Essays on Childhood, Primitivism and Modernism (Princeton University Press, 1998) and When Were Young: New Perspectives on the Art of the Child (University of California Press, 2006) to which he contributed essays. My interest in psychoanalysis also began early with my father, a child psychoanalyst, who taught me about personality and the creative development of children.

Harvard had no studio program or facilities and as an undergraduate I spent nights welding sculpture in an abandoned coal bin under the Radcliffe theater and began writing art criticism for the college paper. In 1966 I won a Jury Award at Sculpture ‘66 in Chicago (I suspect I was accepted because they saw my grey-haired father submit the piece and thought it was his – I was a 19-year-old kid). Also in 1966, I met Andy Warhol at his Boston performance of the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable with the Velvet Underground and Nico” and reviewed it for the Harvard Crimson. My fellow students at the Harvard Crimson, who had no interest in art, taught me to write by insisting that I make my art writing intelligible to them. During the Boston newspaper strike of that year, we became the Boston Crimson and I found myself the only newspaper art critic in town! Two other important influences in college in addition to Rudolf Arnheim were Erik Erikson, who was then writing his psychobiography Gandhi's Truth, and Robert Coles who was writing Children of Crisis, which won the Pulitzer Prize. Bob Coles read and critiqued my Warhol essay for me. Arnheim taught me to see, and Ghandi’s Truth gave me the idea to look at a work of art the way Erikson looked at a charismatic political leader.

I graduated college in 1967 and went off to the Courtauld Institute of Art in London for a two-year MA in art history. In the second year I won a fellowship in art criticism from the Committee on The Pulitzer Prizes at Columbia and with that prize and the help of the Administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, John Hohenberg, I soon found myself writing for The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Christian Science Monitor, and The Chicago Daily News. In London I also reconnected with some of the psychoanalysts who had been my father’s friends and colleagues when our family went there for my father’s work in the late 1950s. I only knew them then as a child, but as a graduate student I began reading D. W. Winnicott and Melanie Klein (both of whom I had met at the age of 11) and began to think about Erikson’s model more broadly in terms of the construction of the self. This became a central aspect of my writing about art, most recently in my book on Modern Art at the Border of Mind and Brain (University of Nebraska Press, 2015), where I make the argument that a charismatic work of art can facilitate the reorganization of the psyche and, following Erikson, that it can create a contagious rethinking on a mass scale, just as Gandhi’s psychological constructions did among his followers. Another intellectual hero of mine, whom I read but didn’t know personally until later, was E. H. Gombrich who was on my M.A. qualifying examination committee at the Courtauld.

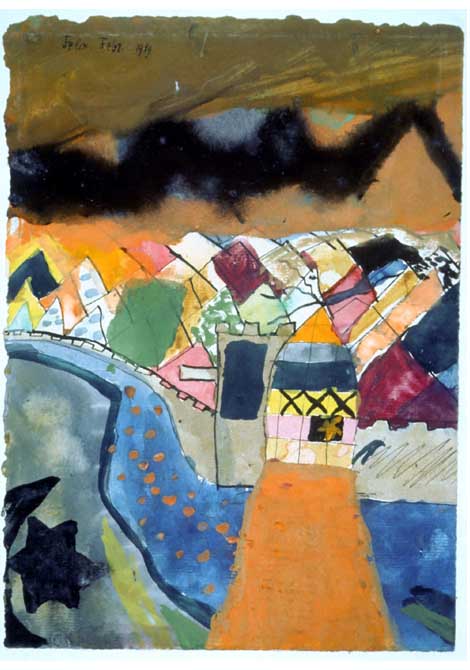

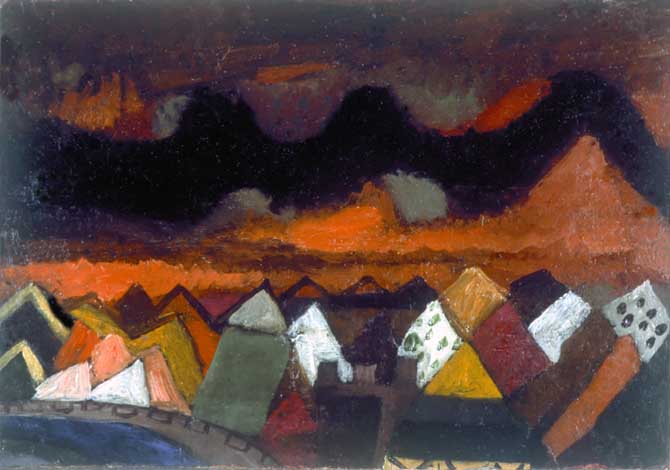

The Innocent Eye: Children’s Art and the Modern Artist

Princeton University Press, 1997

The Innocent Eye: Children’s Art and the Modern Artist

Princeton University Press, 1997

Kabakov

The Serpentine Gallery, London 2005

Zhang Xiaogang

Pace Gallery, N.Y., 2008

The Exploding Plastic Inevitable which I went to at the ICA in Boston and then reviewed.

The Williamsburg Paradigm

Krannert Art Museum, 1993 (a museum show of the young Williamsburg, Brooklyn art scene)

Robert Arneson

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1997

Children’s Art and the Modern Artist

Princeton University Press, 1997

Essays on Childhood, Primitivism and Modernism

Princeton University Press, 1998

A surprise visit from performance artist Paul Cotton (behind us)

Jörg Immendorff

Michael Werner Gallery, New York and Köln 2001

Strategies of Being, 1st edition

Prentice-Hall/Abrams, 1995

New Perspectives on the Art of the Child

University of California Press, 2006

Icons of Twentieth Century American Art

with John Carlin, Yale University Press, 2005